|

(1.3) |

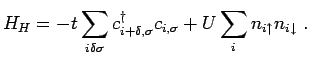

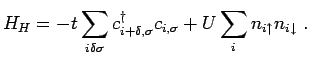

The Hubbard model soon followed the above discussed Kondo model in 1963. Originally intended to model the competition between magnetic and metallic states(10), it has become the standard model in the investigation of strong electron correlation effects in metals. The Hubbard model is defined by its Hamiltonian

|

(1.3) |

This form provides for two important properties of the model. The first term

in the Hamiltonian allows for mobile electrons on the lattice, while the latter

includes an on-site Coulomb interaction between the electrons. This allows for

double occupancy of a lattice site at an energetic expense ![]() as long as the two

electrons don't occupy the same spin state. For the simplest case of only one

orbital, this would correspond to one spin having up spin and the other one

down spin. In its formal simplicity, it is

reminiscent of the Kondo lattice model, and similarly, not all aspects of the problem

have as of now been adequately accounted for.

A physical depiction of these features is shown in

fig. 1.2.

as long as the two

electrons don't occupy the same spin state. For the simplest case of only one

orbital, this would correspond to one spin having up spin and the other one

down spin. In its formal simplicity, it is

reminiscent of the Kondo lattice model, and similarly, not all aspects of the problem

have as of now been adequately accounted for.

A physical depiction of these features is shown in

fig. 1.2.

![\includegraphics[width=3.3in, clip]{Hubbard.eps}](img82.png) |

The model can be quantified by two separate energy

scales. The first is the previously mentioned Coulomb repulsion ![]() , and the

second is the bandwidth

, and the

second is the bandwidth ![]() . The bandwidth is defined as

. The bandwidth is defined as

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of included nearest neighbors. In a regime where

is the number of included nearest neighbors. In a regime where ![]() remains

relatively small when compared to the bandwidth, we expect the electrons to

remain uninhibited and free-electron models apply. If, on the other hand, the

Coulomb repulsion becomes the dominant energy scale and the system is at half filling,

we find ourselves once

again in a regime where electron-electron correlations play a dominant roll.

Hence the classification of the Hubbard as a strongly-correlated electron

model is apparent.

remains

relatively small when compared to the bandwidth, we expect the electrons to

remain uninhibited and free-electron models apply. If, on the other hand, the

Coulomb repulsion becomes the dominant energy scale and the system is at half filling,

we find ourselves once

again in a regime where electron-electron correlations play a dominant roll.

Hence the classification of the Hubbard as a strongly-correlated electron

model is apparent.

In chapter 3, we introduce a novel approach to the Hubbard model. While the methodology takes precedence over the form of the Hamiltonian in our discourse, it is applied to the Hubbard model and constitutes an intriguing new approach to solving the system.